Discussion goals: By placing each work in a historical context, and by considering its technique and materials, students will be encouraged to relate it to shifting societal views of feminine and masculine subjects and definitions of gender-specific poses, body traits, and actions.

Statuette of Hermaphrodite

Hellenistic

Rhodes ?, Greece

Statuette of Hermaphrodite

2nd century B.C.

White marble

149.1 x 27.5 x 13.2 cm (58 11/16 x 10 13/16 x 5 3/16 in.)

Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1922, Fund

2009-81

In classical mythology, the nymph Salmacis loved Hermaphroditos, son of Hermes and Aphrodite. When he bathed in her spring, Salmacis embraced him and prayed that they would never be parted. The gods granted her wish, and the two became a single divine being with both male and female characteristics, most commonly referred to as Hermaphrodite. In this statuette, said to have been found on Rhodes, the god is naked except for a mantle that falls below the male genitals, the latter in counterpoint to the girlish face and the feminine modeling of the body. Leaning against a pillar, she apparently once held a wine jug in her right hand and an offering dish in her left. The figure’s lithe form and sweet sensuality are characteristic of the so-called Rococo phase of the Late Hellenistic period. Another, larger example of this type was found at Pergamon, in western Turkey, a cosmopolitan center whose Attalid rulers fostered the cults of a variety of gods. Such sculptures were not salacious curiosities but objects of sincere devotion, representing the dichotomy of human nature and the yearning for unity in the face of desire.

Conversation prompts

How did the sculptor combine male and female attributes in this statuette? Do you see one gender dominating over the other?

How would you describe the figure’s drapery?

Master of the Greenville Tondo

formerly attributed to Perugino (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci), Italian, 1450–1523

Umbria

Saint Sebastian

ca. 1500–1510

Oil on wood panel transferred to canvas on pressed-wood panel

76.7 x 53.4 cm (30 3/16 x 21 in.)

frame: 99.1 x 75.9 x 8.3 cm (39 x 29 7/8 x 3 1/4 in.)

Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation to the New Jersey State Museum; transferred to the Princeton University Art Museum

1995-330

Saint Sebastian of Milan, a Christian soldier in the imperial army, was marked for execution during the rule of the emperor Diocletian for converting new believers and fortifying martyrs in their faith. Although the emperor ordered Sebastian to be tied to a post and shot with arrows, the saint miraculously survived. Images of this episode, rather than Sebastian’s martyrdom by beating, were used to protect against the plague. Saint Sebastian provided Renaissance artists an opportunity to depict youthful male anatomy. This unidentified Umbrian artist derived the martyr’s pose and anatomical characteristics from Pietro Perugino’s Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian altarpiece in San Sebastiano at Panicale, eliminating extraneous narrative detail. He rendered as a single piercing the bombardment of arrows said to have struck the saint, focusing on one spot that evokes the saint’s efficacy against the plague—the groin, where the black death’s pustules manifest themselves.

Conversation prompts

How would you describe the saint’s pose and gaze?.

What effect does the dark background of the painting have?

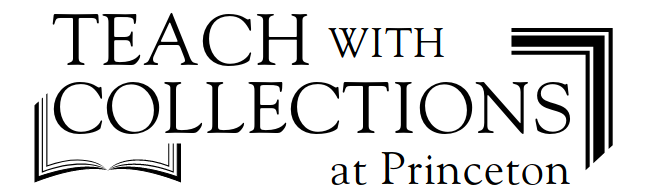

Hans Bellmer, The Mouth

Germany

The Mouth

1936

Gelatin silver print with applied color

16.2 x 16.5 cm (6 3/8 x 6 1/2 in.)

slip-case: 25.1 × 21 cm (9 7/8 × 8 1/4 in.)

Gift of Mrs. Saul Reinfeld

x1983-120

Originally trained as a graphic designer, Hans Bellmer began to create the disturbing, sexually charged scenarios for which he is best known in the early to mid-1930s, shortly after the Nazis came to power. Combining photography, painting, and Surrealist sculpture, these photographic tableaux feature female dolls or mannequins, which Bellmer subjected to a series of disquieting mutations. In this case, the artist fused together two sets of dolls’ legs. Thanks to some suggestive scenography and the addition of pink pigment, these legs evoke both the female pudendum and a mouth (“bouche” is French for “mouth”), uniting the oral and the genital and aligning the processes of communication and consumption with elimination and procreation.

The mannequin figures have been dismembered and reassembled; describe the effect of reading these fragments and the resulting illogical figure.

Conversation prompts

How did Bellmar use color in this photograph?

Bellmer’s works have been praised for their Surrealist vision but also condemned as misogynistic. What is your interpretation, and which details led you to it?

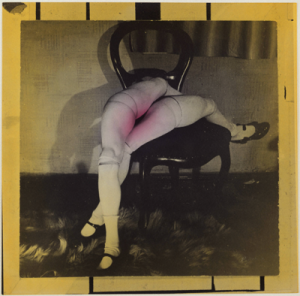

Andy Warhol, Nude Model

Manhattan, New York, New York, United States

Nude Model

1977

Polaroid

image: 9.5 x 7.3 cm. (3 3/4 x 2 7/8 in.)

sheet: 11.4 x 8.6 cm. (4 1/2 x 3 3/8 in.)

Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

2008-260

“A picture means I know where I was every minute,” said Warhol. “That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.” In order to chronicle his every encounter, Warhol carried a Polaroid camera with him from the late 1950s until his death in 1987. As a result, he amassed an enormous collection of photographs—both spontaneous and posed—depicting friends, acquaintances, lovers, art collectors, celebrities, nobodies, and himself. Warhol’s obsession with documenting every moment of his life anticipates contemporary society’s fascination with social media. In this Polaroid from a series of cropped views of a man’s naked body, Warhol captured a model in a pose that both highlights and conceals aspects of his anatomy.

Conversation prompts

What is the significance of the Polaroid medium and the scale of this work?

Describe the pose of the figure and how the artist has played with gender in this work.

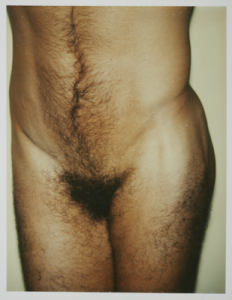

Hannah Wilke, Untitled

Untitled

late 1960s–early 1970s

White terracotta

19 x 16.5 x 12.7 cm (7 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 5 in.)

Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund

2011-115

Hannah Wilke was an influential second-generation feminist artist whose work in sculpture and performance art challenged gender stereotypes and probed the relationship among aesthetics, eroticism, and politics. Wilke began her career as a sculptor, creating pieces in clay and terracotta that evoke both organic forms and female genitalia, a symbol of women’s empowerment in the 1970s. In 1974, Wilke began experimenting with performance art. One of her first forays into this genre was S.O.S. Starification Object Series. As seen in the photographic documentation displayed here, Wilke mimicked an iconic pin-up pose, tempting the viewer’s voyeuristic gaze. The aura of impeccable glamour she projects is disrupted by the pieces of gum—chewed and kneaded to resemble vulvas—that mar her otherwise-flawless back. According to the artist, the gum symbolized women’s second-class status, their “disposability.”

Conversation prompts

Wilke’s pose plays with traditional representations of reclining female nudes. Do you see her disrupting or challenging that tradition? Why or why not?

How did Wilke combine sculpture, performance, and photography? Does one medium dominate over another?

Sample Classes and Checklists

Alessandro Giammei, ITA305_COM375_GSS308: A Gendered History of the Avant-Garde: Bodies, Objects, Emotions, Ideas

Sarah Anderson, ENG 300: Reading Bodies

Judith Hamera, DAN 321: Special Topics in Dance History, Criticism, and Aesthetics – Moving Modernisms: Modern Dance History from 1900-1950