Discussion goals: By placing each work in a historical context, and by considering its technique and materials, students will be encouraged to consider the relativity of color, the effect of different light sources, and the symbolism of light and shadow in different cultures.

With this group of works, it may also be interesting to consider whether each object was created as a multiple, part of a series, or as an independent work, and how that characteristic might affect the viewer’s reading of that work.

Josef Albers, Folder 5, from Formulation: Articulation, Volume 1

New Haven, Connecticut, United States

Folder 5, from Formulation: Articulation, Volume 1

1973

Silkscreen

folded: 38 × 50.5 cm (14 15/16 × 19 7/8 in.)

sheet: 38 × 101.5 cm (14 15/16 × 39 15/16 in.)

Gift of the Josef Albers Foundation

x1975-383.1.5

Albers spoke of color as being relative and changing depending on its environment, stating, “In visual perception, a color is almost never seen as it really is — as it physically is. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art.” Throughout his two volumes of prints, Formulation Articulation, Albers experimented with different compositions and color combinations, as in these two images of nested squares, to create varying illusions of depth and transparency.

Conversation prompts:

Albers’s theories about the relativity of color depended largely upon comparisons between different color combinations. What differences do you notice when shifting your gaze from the nested squares on the left to those on the right?

What is the significance of repetition in Albers’s artistic process?

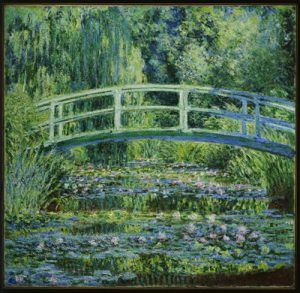

Claude Monet, Monet’s Water Lilly Pond, Giverny, Haute-Normandie, France

Monet’s Water Lilly Pond, Giverny, Haute-Normandie, France

Giverny, Haute-Normandie, France

Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge

1899

Oil on canvas

90.5 x 89.7 cm (35 5/8 x 35 5/16 in.)

Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge represents two of Monet’s greatest achievements: his gardens at Giverny and the series of paintings they inspired. In 1883 the artist moved to this country town, near Paris but just across the border of Normandy, and immediately began to redesign the property. In 1893, Monet purchased an adjacent tract, which included a small brook, and transformed the site into an Asian-inspired oasis of cool greens, exotic plants, and calm waters, enhanced by a Japanese footbridge. The serial approach embodied in this work—one of about a dozen paintings in which Monet returned to the same view under differing weather and light conditions—was one of his great formal innovations. He was committed to painting directly from nature as frequently as possible and whenever weather permitted, sometimes working on eight or more canvases in the same day. Monet’s project to capture ever-shifting atmospheric conditions came to be a hallmark of the Impressionist style.

Conversation prompts:

Monet painted Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge both as part of a series and “en plein air,” or outdoors, with his canvas and easel set up before the scene. How might these aspects of Monet’s technique be significant in thinking about his depiction of light and color?

Looking across the surface of the canvas, what do you notice about the different colors and the thickness of the paint Monet used?

How did Monet depict depth in this composition? Which framing effects did he use?

Late Formative or Early Classic Maya, Shell depicting a marine deity

Maya

Tikal, Southern lowlands, Maya area, Petén, Guatemala

Shell depicting a marine deity

ca. A.D. 200

Spondylus shell with cinnabar

11 x 10.8 x 4.8 x 11 cm. (4 5/16 x 4 1/4 x 1 7/8 x 4 5/16 in.)

Museum purchase with funds given by Carl D. Reimers

y1985-48

Spondylus shells were prized throughout the tropical ancient Americas for their vibrant orange color. This object, possibly a pectoral, was made by carefully shaving away the outer, spiny layer and the white interior of the spondylus and making fine incisions on both sides. The outer surface presents a contorted face with a swollen eye and marine motifs, including a serpent emerging from a spiral shell on the right cheek. The marine motifs may mark the face as that of an unidentified sea deity. A hieroglyphic inscription on the inner surface includes a reference to the great Maya city of Tikal, Guatemala, far from the oceanic source of the shell.

Conversation prompts:

How did the artist use the convex shape of the spondylus shell, its red background, and red lines to create the figure’s face?

In Maya culture, spondylus shells were associated with female genitalia, and their reddish orange hue likely alluded to childbirth and menstruation. What associations might we bring to the color red today?

Li Gongnian, Winter Evening Landscape

Li Gongnian 李公年, active early 12th century

Winter Evening Landscape, ca. 1120

Hanging scroll; ink and light colors on silk

Painting:129.6 x 48.3 cm. (51 x 19 in.)

Mount: 202.5 x 62.2 cm. (79 3/4 x 24 1/2 in.)

Gift of DuBois Schanck Morris, Class of 1893

y1946-191

Li Gongnian served as a prison official in the southern Chinese city of Hangzhou. During the reign of Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1126), the imperial painting catalogue Xuanhe huapu described Li Gongnian’s paintings as “like the shapes of objects appearing and disappearing in vast emptiness, hovering between existence and nothingness.” This painting of mountains in a landscape filled with clouds and mist is the sole surviving authenticated work by him; it is signed and sealed on the rocky outcrop beneath an overhanging cliff at the right. Winter Evening Landscape offers an important link between the monumental landscape style of the Northern Song and the intimacy of the Southern Song (1127–1279). In technique, the stipple strokes used on the mountains are a simplified version of the “raindrop” modeling strokes of the Northern Song painter Fan Kuan (ca. 960–1030). The distant hills dissolving in soft and misty ink clearly anticipate Southern Song styles. Lyricism was a key note in landscape paintings of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and this winter scene with a faint celestial orb in the upper right evokes the poetic line “a winter sun slowly emerges through the mist.”

Conversation prompts:

At first glance, the time of day (evening) and season (winter) depicted may not be obvious. How did the artist convey both?

Is this work from a painting tradition in which artists were fascinated by depicting the play of light? What sorts of artistic devices are important here?

Examples of classes and checklists:

Anya Klepikov FRS 130: Creative Exploration of Color in Life and Art

Taylor PSY 501: Proseminar in Basic Problems in Psychology: Cognitive Psychology

Jane Cox, THR 318 / VIS 318: Lighting Design

David Reinfurt, VIS 216: Graphic Design: Visual Form

Bryan Just, ART267/LAS267/ANT366: Mesoamerican Art