Discussion goals: By placing each work in a historical context, and by considering its technique and materials, students will be encouraged to relate it to questions of face perception, voluntary versus involuntary expressions, and culturally specific versus universal expressions.

In examining all four of these works together, students might also contrast the effect of reading an individual face with reading a multitude of faces.

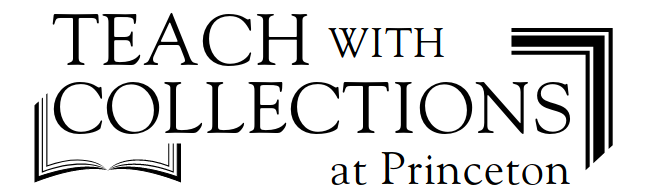

Thomas Rowlandson, Thirteen heads

Thirteen heads

Pen and brown ink over graphite on cream wove paper

22.5 x 18.3 cm (8 7/8 x 7 3/16 in.)

Bequest of Dan Fellows Platt, Class of 1895

x1948-1664

Rowlandson’s wide-ranging depiction of extreme expressions in this radiating cluster of heads speaks to his fascination with translating human emotions into a linear vocabulary decipherable by a viewer. Each of the heads on this sheet evidences the artist’s ability to significantly alter the effect of a figure’s face through subtle alterations to the pen lines. A key influence on such investigations into different facial arrangements was Charles Le Brun’s lecture at the French Académie in 1688—later published with illustrations as Conférence sur l’expression générale et particulière—which attempted to codify specific facial movements in relation to particular passions.

Conversation prompts:

Consider the medium of pen and ink and describe the varying lines used by Rowlandson; with which facial features do you see him experimenting most?

Why might the juxtaposition of heads be important in studying expression? Do these multiple heads relate to one another?

Compare this grouping of heads with those in Duchenne’s photograph: how do the media and the organization of heads differ between the two works? What effect does this have on the viewer?

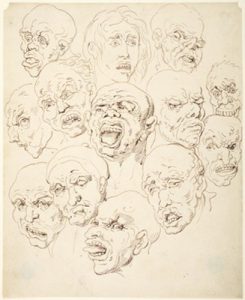

Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne, Plate from Mechanisme de la Physionomie Humaine

Adrien Tournachon, French, 1825 – 1903

Plate from Mechanisme de la Physionomie Humaine

1862

Albumen print

13.1 x 10.8 cm. (5 3/16 x 4 1/4 in.)

mount: 27.7 x 18.1 cm (10 7/8 x 7 1/8 in.)

Museum purchase, anonymous gift

1995-134

The French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne was the first person to empirically test the idea that emotional expressions can be understood as movements of facial muscles, an idea now taken for granted. Duchenne applied electrical currents to facial muscles and used newly invented photographic techniques to record the movements of the face. His research influenced Charles Darwin and generations of modern psychologists. The most popular coding system at present, the Facial Action Coding System, used for classifying emotions in psychology and computer science, is partly based on Duchenne’s research. This plate shows photographs of expressions after stimulation of the corrugator supercilii, one of the muscles controlling the eyebrows. Duchenne believed that this muscle completely controlled expressions of pain. By covering half the face, he could demonstrate that the expression was due to local movements of the eyebrow rather than movements across the whole face.

Conversation prompts:

As Rowlandson did, Duchenne presents the viewer with numerous faces on which to examine expressions. How would you compare these expressions to those illustrated by Rowlandson?

How would you describe the arrangement of the heads in Duchenne’s work? Does this arrangement influence your reading of the faces? If so, how?

Did your reading of Duchenne’s work shift once you knew it was part of a scientific experiment?

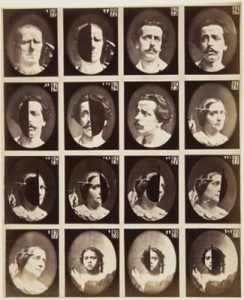

Diane Arbus, A Child Crying, N.J.

A Child Crying, N.J.

1967

Gelatin silver print

image: 37.3 x 38.5 cm. (14 11/16 x 15 3/16 in.)

sheet: 50.6 x 40.5 cm (19 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

Gift of Howard and Katia Read

x1994-124

This 1967 photograph by Diane Arbus shows a close, cropped view of a child crying. Arbus became well known for her particularly individualistic portraits that challenged what was considered acceptable as subject matter and the proximity of a photographer’s gaze. Some critics described her photographs as voyeuristic; others praised her for her empathy.

Conversation prompts:

Is this an image that invokes our empathy? Why or why not?

Which particular features do we look at to determine that this child is crying?

Arbus has excluded any background for this figure’s emotional reaction; how does the lack of context influence our reading of the scene?

Pende artist, Female mask (gambanda)

Kwango Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Kwilu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Female mask (gambanda)

before 1924

Wood, raffia, paint, and dye

h. 33.0 cm., w. 22.5 cm., d. 17.0 cm. (13 x 8 7/8 x 6 11/16 in.)

Gift of Mrs. Donald B. Doyle in memory of her husband, Class of 1905

y1953-139

The Pende word for “mask” is mbuya. Mbuya encompasses not only the mask but the entire masquerade complex, including costume, song, dance, ritual, and other aspects of performance. Masks depicting women may be known as Gambanda or Kambanda (Wife of the Chief) and can also refer to the entire category of female masks, some depicting the “contemporary fashionable woman.” The artist who made this mask paid careful attention to depicting the hairstyle and the woman’s expression. The eyes have heavy lids: they are known as zanze, and their shy, seductive gaze is roughly equivalent to what we call “bedroom eyes.” This mask also presents idealized female facial features: a large, smooth forehead; sharp cheekbones accentuated by curved scarification marks; and a close-lipped mouth. Combined, these facial features and this expression demonstrate the Pende belief that women are more emotionally peaceful than men.

Conversation prompts:

Describe how the artist rendered facial features, paying attention to the use of different materials and colors.

What were your immediate impressions of the facial expression on this mask? Have they changed after learning how the Pende interpret them?

How do cultural conventions about expressions affect our interpretations?

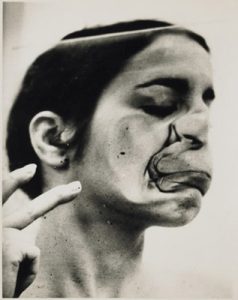

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints – Face)

United States

Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints – Face)

1972

Gelatin silver print

image: 24.3 x 19.5 cm. (9 9/16 x 7 11/16 in.)

sheet: 25.4 x 20.3 cm. (10 x 8 in.)

Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund

2007-41.8

To create these images Ana Mendieta pressed a piece of glass against her face and different areas of her naked body and then photographed the results. She later selected the thirteen images seen here—all depicting her face—and sent them to a lab to be printed as a series of black-and-white photographs. This piece is one of Mendieta’s earliest experiments with body art, made while she was still a student at the University of Iowa. Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints – Face) is an artwork in two parts: the performance of the actions through which Mendieta asserts control over her body by subjecting it to pressure, and the documentation of the distortions of her features. These photographs affirm Mendieta’s agency as much as they record the violent pressure and resulting discomfort as she manipulates her body before the camera. Such experimentations, which served as evocative metaphors for the discrimination she faced as a Cuban American and female artist, ended when her life was cut short in 1985.

Conversation prompts:

Consider the different ways in which Mendieta positioned herself against the glass to alter her appearance.

What is the significance of this work as a performance captured through a series of photographs?

Many art historians read Mendieta’s work as a commentary against the societal biases she had experienced as a Cuban American female artist. Which details in the work support or challenge this interpretation?

Shunkōsai Hokuei 春梅斎北英, Mitate: Arashi Rikan II as Hachiman Taro and Nakamura Utaemon III as Abe no Sadato (見立 「八幡太郎」二代目嵐璃寛、「安部貞任」三代目中村歌右衛門)

Edo period, 1615–1868

Shunkōsai Hokuei 春梅斎北英, active 1829–1837

Japan

Mitate: Arashi Rikan II as Hachiman Taro and Nakamura Utaemon III as Abe no Sadato (見立 「八幡太郎」二代目嵐璃寛、「安部貞任」三代目中村歌右衛門)

1832

Woodblock print (ōban yoko-e format); ink and color on paper

sheet trimmed to block: 26.5 x 39.3 cm. (10 7/16 x 15 1/2 in.)

mount: 31.7 x 44.5 cm

Museum purchase, The Anne van Biema Collection Fund

2011-92

This woodblock print from Osaka focuses on a close view of Kabuki actors against an abstract background. Hokuei presents two actors who performed together during their careers, although never together in these roles. The imaginary scene showcases the characters’ exaggerated theatrical expressions, which are further enhanced by the use of traditional white makeup along with black and red face paint. Such drawn marks transform the actors’ faces into animated masks, allowing spectators observing them from a distance to identify the characters portrayed and to understand each character’s emotions throughout the narrative.

Conversation prompts:

Which features of the figures’ faces have been particularly highlighted by their face paint?

Do you read these expressions as extreme? Why or why not?

Examples of classes and checklists:

Alexander Todorov PSY 411: Psychology of Face Perception

Monica Huerta ENG 319/ AMS 322: About Faces: Case Studies in the History of Reading Faces

White/Riihimaki FRS 114: Invention and Innovation: Intersections of Art and Science