Discussion goals: By placing each work in a historical context, and by considering its technique and materials, students will be encouraged to relate it to questions of different historical perspectives and contemporary reinterpretations of historical figures and events.

Titus Kaphar, To Be Sold

To Be Sold

2018

Oil on canvas with rusted nails

152.4 × 121.9 × 8.9 cm (60 × 48 × 3 1/2 in.)

with strands: 248.9 × 121.9 × 8.9 cm (98 × 48 × 3 1/2 in.)

Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund

2018-83

On July 31, 1766, the headline “To Be Sold” announced the sale of six African American slaves on the site of Princeton University’s Maclean House, as part of the dispersal of the estate of Samuel Finley, president of the University from 1761 to 1766. Kaphar’s work responds to the archival records of this sale, affixing with nails the tattered strips of a painted enlargement of that advertisement along the contours of a portrait bust of Finley. The contemporary work merges two traditions: honorific oil-portrait busts and Kongo power figures (minkisi). To Be Sold aims to invert the relationship between the entrenched heroic image of a founding father, the typical subject of historical memory, and the enslaved human who remained unseen and unknown.

Conversation prompts

Kaphar is known for his study of traditional American and European art, especially of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and his interest in amending history. How does this work transform the traditional genre of portraiture? What effect does this transformation have on the viewer?

Which materials and techniques does Kaphar combine? How do they complement (or contrast with) one another?

Describe the relationship between what is visible and invisible in this work.

Carrie Mae Weems, From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried

House/Field/Yard/Kitchen, from the series From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried

1995–96

Chromogenic prints with sandblasted text on glass

each frame: 67.3 × 57.8 cm (26 1/2 × 22 3/4 in.)

installed: 139.7 × 119.4 cm (55 × 47 in.)

Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund

2016-378 a-d

In House/Field/Yard/Kitchen, which is part of the series From Here I Saw What Happened . . . And I Cried (1995–96), Weems looks to the past to better understand the present. A thirty-three-piece photographic installation, this series appropriates nineteenth-century images of slaves as well as other nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographs of Africans and African Americans, the originals for which are in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s collection. Among the source images Weems reworked are those produced in 1850 by Joseph T. Zealy, a well-known portrait photographer from South Carolina. These daguerreotypes were commissioned by Louis Agassiz, the Swiss American biologist, geologist, and polygenicist who believed that each race was created separately and could be classified by particular physical attributes. Denying their subjects any markers of individuality, the Agassiz–Zealy photographs scientifically objectified enslaved Africans, turning them into specimens. As Weems points out, a similar distancing happens with all of the appropriated images, not only the daguerreotypes: “When we’re looking at these images, we’re looking at the ways in which Anglo America—white America—saw itself in relationship to the black subject. I wanted to intervene in that by giving a voice to a subject that historically has had no voice.” By taking such images, toning most of them in a blood-red glow, and inscribing text across the surface of their glass, Weems aims to undermine the dehumanizing effects of historic images of African Americans and to invite subsequent reconsiderations of contemporary perceptions.

Conversation prompts

What specific stylistic changes did Weems make to the original photograph? What effect do these changes have?

Weems has described photography as “a powerful weapon toward instituting political and cultural change.” Do Weems’s photographs succeed in granting a voice to those who were previously silenced? Why or why not?

How does each figure’s gaze influence your reading of the photograph?

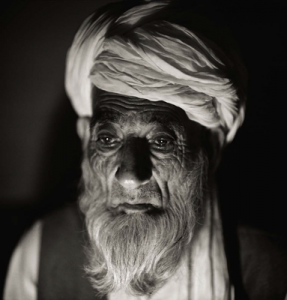

Fazal Sheikh, Rohullah, Afghan refugee village, Badabare, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Rohullah, Afghan refugee village, Badabare, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

1997

Inkjet print

image: 61 × 61.3 cm (24 × 24 1/8 in.)

sheet: 91.4 × 80.6 cm (36 × 31 3/4 in.)

frame: 76.8 × 76.4 × 3.8 cm (30 1/4 × 30 1/16 × 1 1/2 in.)

Promised gift of Liana Theodoratou in honor of Eduardo Cadava

L.2017.48.6

Long concerned with documenting people living in displaced and dispossessed communities, the artist Fazal Sheikh, Princeton Class of 1987, selected this photograph, among others, for exhibition in response to President Donald Trump’s Executive Order 13769 of January 27, 2017. The order blocked entry into the United States for citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries—Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen; indefinitely barred refugees from Syria; and suspended all other refugee admissions for 120 days. This photograph exemplifies Sheikh’s continuing efforts to amplify the stories of marginalized people through images and texts. The conjunction of Rohullah’s photograph and the accompanying text below offer a compelling voice for Sheikh’s humanitarian project.

“In 1981 my cousin, Qari Monir, was taken along with thirteen other elders and mullahs by communist troops into the desert. For six months the villagers did not know what happened to them. Then one day a shepherd minding his animals in the desert area surrounding the village saw a piece of white cloth under the earth. He pulled at it and finally he realized that it was a long scarf. As he continued to dig he saw that there was a man buried there. . . Eventually, the fourteen bodies of our leaders were recovered. Their hands and feet had been tied and they had been buried alive. . . These were spiritual people and they were awaiting a proper and respectful burial. It was this incident which convinced us that the communists were willing to kill us all, not just those who were fighters. And so we decided to leave the village and take our families to the safety of Pakistan. In the months that followed, the men returned to Afghanistan to free our country from the invaders.”

Conversation prompts

Describe the cropping effects, angle of vision, and focal points of the composition. How do these elements inform your interaction with the figure?

What type of relationship would you imagine between the artist and the sitter based on the style of this photograph?

Does this figure appear to be a marginalized figure in society? Why or why not?

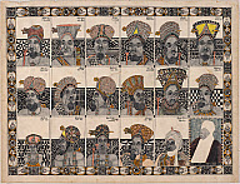

Ismail Tita Mbohou, Genealogy

Bamum Kingdom, Department de Noun, Region de Ouest, Cameroon

Genealogy

after 1952

Ink and pencil on paper

frame (approx.): 35.6 x 50.8 x 3.2 cm (14 x 20 x 1 1/4 in.)

Gift from the Holly and David Ross Collection

2015-4

The Cameroonian ruler Ibrahim Njoya invented a new genre of secular art—drawing on paper—to depict the history and culture of the Bamum Kingdom. These dessins bamum (Bamum drawings) were created in multiples to allow for wide distribution, and include captions written in German, French, or Shüpamom (the Bamum language, of Njoya’s invention) to better reach different viewers. This drawing presents the royal genealogy of the Bamum kingdom of Cameroon from its 1394 foundation to sometime after 1933. Eighteen Bamum rulers are depicted with distinctive headgear as well as elaborate necklaces, bandoliers, and staffs. The first seventeen pose in front of the geometrically patterned walls of the palace at Foumban; the last is placed against a gray background, indicating that the image was influenced by a much-reproduced studio photograph of that leader. Bamum genealogies affirmed dynastic lineage and promoted official history during a time of internal and external power struggles, including intra-kingdom disputes and European colonialism.

Conversation prompts

How do dessins bamums combine old and new forms of Bamum art and culture?

In which language are the captions of this drawing written? Why would the Bamum have wanted to appeal to the speakers of that language in the 1930s, when this drawing was made?

Sample classes and checklists

Christopher Achen, FRS 101: American Politics in the Age of Donald Trump

Nijah Cunningham: AAS 392 / ENG 392: Topics in African American Literature – Fictions of Black Urban Life

Christina Leon, ENG 416 / AMS 416: Topics in Literature and Ethics – Minority Literatures and Ethical Reading