Discussion goals: By placing each work in a historical context, and by considering its technique and materials, students will be encouraged to reflect on shifting views of the environment, art as activism, and different relationships between humans and the environment.

In considering these works, it might be interesting to reflect on the inclusion of human figures and their placement in the landscape, or the effect of the exclusion of figures from a landscape.

Vik Muniz, Narcissus

United States

Narcissus

2005

Chromogenic print

sheet: 222.5 × 178 cm (87 5/8 × 70 1/16 in.)

frame: 234 × 189.5 × 5 cm (92 1/8 × 74 5/8 × 1 15/16 in.)

Museum purchase, David L. Meginnity, Class of 1958, Fund

2006-94

To make the photographs in the series Pictures of Junk, Muniz manipulated refuse and metal detritus on the floor of his workspace in Rio de Janeiro. The junk was reconfigured to resemble Old Master narrative paintings as well as portraits of the catadores (garbage collectors) whose livelihood depended on scavenging in Jardim Gramacho, one of the world’s largest dumps. For this work, Muniz perched with his view camera on scaffolding high above the floor and used a laser pointer to direct studio staff (including local art students) in arranging the trash into the form of Caravaggio’s Narcissus (ca. 1597). Muniz’s illusionism reminds us that all picture-making is a process of reflecting and recycling that turns mere materials into stuff of the mind or of art.

Conversation prompts

Which objects do you notice first when looking at this work? Which come into view later, and how does your reading of the work shift when they do?

What different types of artwork does this object combine? How does it break down the boundaries between different artistic media, such as sculpture, photography, and performance art?

Does the use of recycled materials here imply that the environment is resilient or fragile?

Michael Kenna, The Rouge, Study 59, Dearborn, Michigan

Dearborn, Wayne County, Michigan, United States

The Rouge, Study 59, Dearborn, Michigan

1994, printed 1996

Gelatin silver print

20.2 x 18.9 cm. (7 15/16 x 7 7/16 in.)

mount: 50.8 x 40.6 cm. (20 x 16 in.)

The Ford Rouge Complex Collection, gift of the Ford Motor Company

1997-29.59

From its origins—developed by Henry Ford, working with his house architect Albert Kahn, for the Ford Motor Company between 1917 and 1927—the Rouge became a vast complex containing miles of railroad tracks, blast furnaces, coke ovens, a foundry, and enormous storage areas for holding the raw materials to be used in manufacturing—a veritable city unto itself for the industrial age. Across more than a dozen visits between 1992 and 1995, Kenna sought to depict the enormity of the Rouge, often under arduous conditions of extreme cold. His work at the Rouge employs a number of key strategies: an interest in photographing under low-light conditions and even at night; a concern for reflections and the image doubling they create; a fascination with the contrasts between the strong linearity of the built environment and the effacing atmosphere around it; and the absence of people.

Conversation prompts

Kenna used radical cropping effects and an extreme point of view for this scene. What effects are created by these compositional devices, and how might the effect of the work have been different had Kenna taken the photograph from a head-on perspective?

There are no human figures in Kenna’s series of photographs of the Rouge; how do you read the relationship between humans and the environment in these photographs?

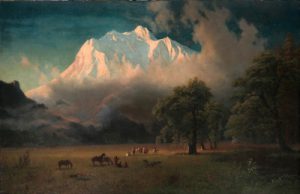

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Adams, Washington

Mount Adams, Washington, United States

Mount Adams, Washington

1875

Oil on canvas

138 x 213 cm. (54 5/16 x 83 7/8 in.)

frame: 180 × 255.7 × 15.5 cm (70 7/8 × 100 11/16 × 6 1/8 in.)

Gift of Mrs. Jacob N. Beam

y1940-430

Albert Bierstadt enjoyed great success in the years surrounding the Civil War by producing finely detailed vistas of nature’s splendor on majestic canvases that were invested with a significance beyond their surface appearance. The first technically advanced artist to portray the American West, Bierstadt offered to a rapidly transforming nation pictures whose spectacular size and fresh, dramatic subject matter supplied a visual correlative to notions of American exceptionalism while contributing to the developing concept of Manifest Destiny. Bierstadt was trained in the highly finished manner of the Düsseldorf Academy, and his precise style imbued his works with a reassuring sense of veracity that their sublime subjects and his occasional liberties with geographic reality would seem to belie. In Mt. Adams, Washington, the artist characteristically combined an impressively scaled natural background with a foreground view of American Indian life, which serves to heighten the picture’s putative realism even as it enhances its exotic appeal.

Conversation prompts

What do you find to be the focal point of the composition? How does Bierstadt guide your gaze through the composition?

How would you describe the depiction of the figures in the painting? What effect might this have on contemporary viewers’ understanding of the western landscape?

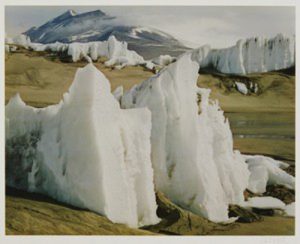

Elliot Furness Porter, Remnants of Wright Lower Glacier

Remnants of Wright Lower Glacier

1975, printed 1984

Dye transfer print

24.6 x 30.8 cm (9 11/16 x 12 1/8 in.)

mount: 38.1 x 45.7 cm. (15 x 18 in.)

Gift of the artist

x1984-280

Elliot Furness Porter worked as an instructor and researcher in the Department of Biochemistry and Bacteriology at Harvard and Radcliffe College while also pursuing his long-standing interest in photography. He became widely known for his use of the dye transfer technique to create vibrant color photographs of the natural world. Several of Porter’s portfolios and photography books—including In Wilderness Is the Preservation of the World, published in 1962 by the Sierra Club—raised awareness about environmentalist causes.

Conversation prompts

What effects do the bright colors used by Porter have on the subject matter? Contrast his color photograph with Michael Kenna’s black-and-white photograph.

How proximate to his subject matter was Porter? How does his perspective affect the viewer’s reading of the photograph?

Sample Classes and checklists

Daniel M. Sigman GEO 102A / ENV 102A / STC 102A: Climate: Past, Present, and Future (Labs, Danielle Schmidt)

Kelly K. Caylor David S. Wilcove ENV 201B / STC 201B: Fundamentals of Environmental Studies: Population, Land Use, Biodiversity, and Energy (Labs, Catherine Riihimaki)

Chad Monfreda, ENV 348 / ARC 348: The Modern Environmental Imagination: People, Place, Planet